I have a rather puzzling story that perhaps is indicative of some of what ails the world today.

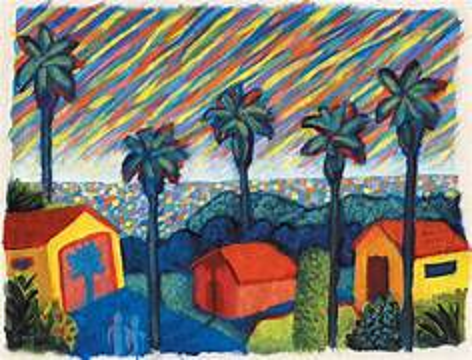

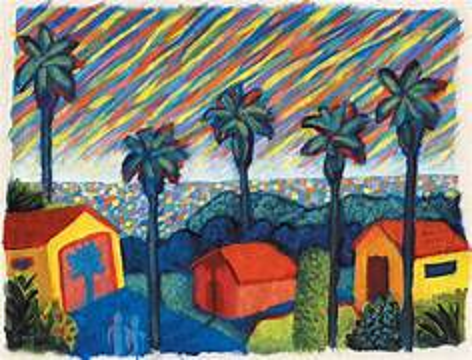

I have a new lady (Catherine Lee Neifing) in my life who has been an accomplished artist for most of her life. Most of her works are standard paintings on canvas, some are three-dimension constructions, and then there are the many sketch books and other media. Over the years she has accumulated hundreds of these works – selling many prints, selling some originals, but keeping many of the larger and more spectacular paintings.

Here are a couple small images of some of her paintings.

If you are interested, you can view many more on her website https://www.catherinelee.com/

Unfortunately, her works are stored away in a garage and her studio in a way that makes them difficult to view. For example, many of her larger (4 ft by 6 ft or larger) works are rolled up for storage and are therefore not readily accessible. There are stacks and stacks of paintings, prints, sketches and other things – all of which I want to someday see and experience. I have seen glimpses of some of her “hidden” work that totally blow me away – they just sort of stop me in my tracks and mesmerize me as I stand and absorb the “vibes” of the image. Many are “just” paintings, but quite a few grab me by the short hairs on my neck and make me pay attention.

I recently purchased an old house in the town of Sonoma (think wine country) in California. This old house cries out for “art” to set the mood but is just too small to display more than a few paintings. Therefore we have been looking for a place to unpack her work and hang them for display. We have been looking for a space that has enough walls to hold the works, is protected from the environment, suitably lit, and secure. Many of the items are not framed or stretched, some have small damage needing repair and some are unfinished works. This results in a requirement for a rather large space to house the materials, and provide room to work. Not only do we need sufficient wall area, but we need to have the ability to light the art in order to properly view the objects.

Our goal is to create something like a temporary gallery displaying some of her work. We don’t anticipate opening the gallery to the public, we just want to see it to figure out what to do with it. I have a sense of urgency about this project because our time is clearly limited. She is 75, I turn 78 this weekend. The question before us has to do with figuring out what to do with all of this work. If she just ignores it, her two boys will inherent the art- but what are they going to do with it? They can’t fix the items that are damaged or incomplete and most likely will not have the ability or desire to do much of anything with it. Then what? It seems better to sort it out now, while Cathy is able to assist in the project of sorting out the good from the not-so-good, and trying to figure out their future homes. Perhaps some can be sold, perhaps some might be displayed somewhere – it is all a mystery to me.

In any case, we have been searching for a suitable building that we can afford to rent for awhile as the works are hung, sorted, fixed and enjoyed. For a little while we had a fantasy of perhaps paying for this space by opening a gallery where she could sell some of the works. This approach might have the advantage of paying for itself, while getting her materials once again out into public view. After all, what good is art if nobody sees it? Art is meant to be viewed and enjoyed, not rolled up in the dark corner of a garage somewhere.

We found a couple suitable empty stores on the Sonoma Plaza – but of course these were pretty expensive, meaning that the “sales” aspects of the store would become the focus rather than meeting our needs to view and figure out what to do with her work. The more I thought about it, the more it became obvious that we would be taking on a bigger project than we are prepared to do, and in the process would likely miss doing what we want to do.

We had just about given up hope when we found out about a big old building a 1/4 of a block from the plaza that might meet our needs. It is a rather odd building, perhaps three stories high but with access only to the first story. In effect, it has a ten foot ceiling and a HUGE unaccessible attic. I don’t know the age of the building, but my guess is it is probably from around the 1880’s. Covered in rusting corrugated metal siding, sporting a filthy canvas awning over the front entrance- with a tiny grungy toilet and not much else. The building has been unoccupied for the past ten years and has been allowed to deteriorate as it sat forlorn next to the main street through town. However, it is just right for us. It is inconspicuous and unnoticed, giving it a bit of security. There are few windows, making it easy to install security devices. There are track lights suspended from the ceiling installed by the previous tenet making it easy to light. And it has lots of space for displaying art and setting up a small workshop. It is ugly and filthy, but perfectly suited for our needs.

It turns out that the reason that it sits empty is that it is located on the site of a future new hotel. Once the owner gets permission to build the hotel, the building will be demolished. The temporary nature of the availability, and the state of decay of the building, makes it unrentable as a normal business. It is just sitting there, creating a tax and insurance liability – waiting to be demolished. This is fine with us, we are looking for a temporary location for just about the same amount of time as the owner thinks it will take to finish getting permission from the city to build his hotel. We don’t care that the building is ugly, or that parking is difficult – we don’t want or expect any public traffic. We don’t care that the floors are terrible, or that the walls need painting. None of those things that would normally be required to create a serviceable store are required. We just want weather proof, secure space.

We got a tour of the building by the owner’s agent. It all looked great. When I asked how much it would cost, he suggested that I make an offer. I offered $1,000 a month for a month-to-month lease that could be terminated at will by the owner once his project was ready to move forward. In some ways this was a ridiculously low offer for a 2800 square foot building in the very popular center of town in Sonoma. I was offering about $0.30 a square foot for space that would normally rent for around $10.00 a square foot if it was rentable – but in this case it isn’t rentable (as evidenced by sitting empty for more than ten years). A thousand dollars a month just to look at Cathy’s work is expensive for us, but it seems like fun and worth the money. Of course, it is a tiny fraction of what the building would be worth if the building was worth anything – which it isn’t. The property is worth $1M (or more), but the building is worth less than nothing because it will have to be torn down to be usable at all. My logic for my low offer was that while it wouldn’t make much of a “profit” for the owner, it would generate a small amount of income to partially offset some of the costs of maintaining an empty building, and would help out an artist that could make use of the building – without adding extra costs for the building owner. We would of course cover the costs of things that we needed such as electricity, renter’s insurance, etc.

The agent took my offer to the owner, and it wasn’t rejected outright! That surprised me – I expected a flat “no.” Instead of a “no” we were told that they were working on a lease agreement. We were excited – it looked like we were going to be able to start our project soon.

However, when we got the paper work for the lease it was much different than my offer. First off, it wasn’t a month-to-month at $1000 a month, it was six months for $6000 followed by a month-to-month at $1700 a month! What??? Why the big jump? Then it turns out that they were proposing a variation of a triple-net lease – but without any information about how much that might cost.

A triple-net lease is one where the lessee pays some amount for rent (in this case $1000 a month), but also pays ALL of the expenses for the property. These extra items include things like property taxes, the property owner’s attorneys fees, accounting fees, tax preparation, building insurance, etc, etc. The outcome is the building owner pays nothing because the lessee pays for it all and also pays rent. This is a normal form of most commercial leases these days – which I generally agree are “fair.” Obviously the lessee will end up paying for all of the expenses for the building. As a property owner I would set my rates to cover all of my expenses plus whatever “profit” I think I can get. Any unmet expenses will have to come out of the “profit” – but they will be met. Nobody wants to have a business where they lose money as an intended outcome.

However, in this particular case it is a bit different. In this case all of those additional expenses are being paid by the owner if it is not leased – and there is little or no potential for renting the building. The building has been creating a net loses for the owner for over ten years and will continue to do so until such time as it is demolished. My offer was a net “increase” in profits in the sense that it offsets ongoing loses.

I think we had a win-win deal in our hands. I would get a place that meets our temporary needs at a price that I am willing to afford; they would get a very flexible temporary tenant willing to vacate when needed. They make a few bucks while maintaining their flexibility, we get an affordable space to evaluate and plan for what to do with Cathy’s art. However, rather than that, the owner decided to offer a deal that would cover all of their costs and create a true profit. Not only that, but they didn’t give me a hint of how much those additional costs might turn out to be – they expected me to sign a blank check for whatever they might decide to charge me in the future. I assume that would be at least double what I offered, but perhaps much more. I of course walked away from the “deal” – it was no deal for us.

At first I was a bit insulted by the response, then I realized that it wasn’t an insult of any sort – it was just a “business as usual” sort of thing. As I have been pondering this situation for the past couple of days I realize that there is something more here that seems really important to what is happening in the world today. There is a much larger importance to the owner’s desire to throw away a small income by demanding a much larger profit (that is impossible for them to get). They must have known that I wouldn’t accept their counter offer – it was just too far away from my offer. Knowing this they decided that it would be better to keep losing money than to give someone a break.

There is something deeply unsettling about this approach to doing business. Instead of accepting an offer that would make some money a decision was made to demand unacceptable rates. Maybe what is unsettling is that the “give and take” of bartering is missing. Our economy used to be based upon the notion of mutual agreement concerning the value and cost of things – originally implemented by face-to-face bartering. This worked when there was a fair distribution of goods. It didn’t work when one party had all of what was needed and therefore the “power” between the participants was uneven. Monopolies where one person controls all of a much needed commodity fail the “fairness test” and therefore result in great unfairness in the market place. It turns out that the owner of the property that I was seeking also owns much of the commercial real estate in town. If you want to get a space in that area you will just have to meet his price. There is no incentive, or desire, to negotiate or determine actual value or exchange.

That seems to be where we are now in the global economy. We keep getting impacted by things that are blatantly “unfair” but might makes right, so we pay what we have to pay. For example, prices rise when a supply shortage occurs just because they can be raised, but they do not return to the original value when the shortage no longer exists. Those in power change what they want, and you either take it or leave it. There is no “working together” involved, it is all about taking as much as you can get regardless of the impacts to others – often referred to as greed. This is how very large businesses became so insanely rich. Microsoft didn’t create billions of dollars in profits because their product was difficult to make, it made those profits because it cornered the market (with a virtual monopoly) and changed as much as they could get. As we became more and more dependent upon technology large businesses just kept raising and raising their profit margins because they can. This is now the world order, how else could the cost of telephone service have risen to hundreds of dollars a month – we HAVE to have it now, so we pay whatever it costs. As long as we can pay that much, then they will change that much.

My question is whether or not we can sustain a situation like this. As a business person, my goal was to produce a service/product that gives me a reasonable return on my investment. For example, I think a profit on the order of 10% of my annual sales would be marvelous. When I was in the residential solar business I was thrilled by the ability to make 5% profit on a sales. This means that if it cost me $10,000 for a system, I would change an additional $500 “profit.” That doesn’t seem like much, but since all my expenses were covered by the cost of the system, it was a huge source of income. I was just a small three person business, typically installing two systems a week. That is about 100 systems a year. At $500 a system in profits, that netted me $50,000 a year in profit (after all of my expenses including my labor) from a business that had close to zero capital – it was all labor and borrowed product (I would purchase the equipment on credit, get paid before the bill came due, so never actually had to pay for anything out of my pocket). Was I being “greedy” by changing this much in profit? Possibly, it certainly made a lot of money for me. However, the system that I sold for $10,000 was normally sold by my competitors for $20,000, with an estimated profit of $500,000 a year! The reason that solar contractors can get away with such huge profits is that solar is so cheap and so effective that even the high prices get “paid back” in ten years (mine got paid back in five years). It is a “good” business decision for the customer – and therefore “what the market will bear” creates massive profits for some. Can we run a world like that?

I don’t know how we fix this problem, but it is very clear that setting prices because something is “worth it” results in massive divisions of wealth. As technology advanced, the idea of pricing based upon what something is “worth” instead of what is “costs” to create is upsetting the world order. I don’t think that it is feasible to legislate price controls based upon some arbitrary profit margin, but I am certain that the current unbridled greed based business practices will eventually end up killing the chicken that lays the golden egg.