Last year the California Public Utilities Commission (CAPUC) ruled that the current rate structure for residential solar is “unfair” for those that don’t have solar. Apparently, those who are too “poor” to afford solar have been subsidizing the cost of electricity for those who are “rich” enough to install solar. Their argument didn’t include things like the ongoing California subsidy program that provides lower income folks with free solar installations, or consider the fact that the “poor” folks are exactly those that could have benefited the most from lower utility bills associated with installing solar. Lower income homeowners can get solar for free. Perhaps the concern is that renters can’t easily reap the economic benefits of solar because landlords aren’t likely to invest in solar and pass the savings along to them. Actually, I don’t think there is actually a concern about “fairness for the poor” – rather it is about increased profits for the utilities. Solar installations are finally becoming numerous enough that it is impacting the economic model for the utilities, it is no longer just a nuisance, it is changing their business model. Luckily for them, the California Public Utilities Commission (PUC) is packed with commissioners coming directly from the utilities who agree that big utility businesses really should get a larger share of the reduced costs for solar power.

The new rate structure reduces the value of “extra” power produced by residential solar installations during periods of excess production – a reduction of approximately 75% from previous rate schedules. An important feature of the old (NEM 2.0) rate schedule was that extra power was delivered to the utility by running the meter backward. Thus a kilowatt delivered to the utility in the middle of the day could be “used” to offset a kilowatt of power used at night (or at a different time of the year). The idea was to “loan” the utility some power until you needed it later. This is known as “net metering.” This approach caused all sorts of complications because of the different rate schedules between day and night use, the utilities “bought” high valued day time power and sold it as low valued night time power, giving them a substantial (letting them make about 24% on the cost of the “loan”) profit from the transaction but apparently this was not sufficient. [For example. A common Time of Use rate is $0.63/kWhr during the day when extra solar is produced and $0.51/kWhr off peak during the night, giving them a 124% markup on power provided by residential customer owned systems.]

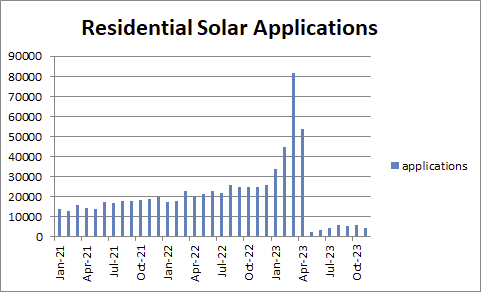

The new rate structure reduces the financial advantage of solar power, extending the “pay back” period for solar installations, therefore resulted in a huge reduction in the number of new solar installations. What was a “good deal” for the utilities and the homeowners has now become a great deal for the utilities and not such a good investment for homeowners. Too many people were enjoying the benefits of locally produced solar electricity. The impact can be seen in the graph showing residential solar applications over time (the new law come into effect in April 2023). The reduction from an average of about 20,000 installations per month to perhaps 1,000 per month represents a major loss of jobs for installers, a huge loss of sales for equipment providers, and a potential loss in renewable energy (supposedly an important goal for California).

Source: https://www.californiadgstats.ca.gov/downloads

The “problem” that they were trying to “fix” is that since the cost of the utility infrastructure (the cost for things related to transmitting the power) is embedded in the cost of purchasing a kW of power, those that don’t use kWs because they zero out their annual usage through solar net metering don’t pay for the cost of the infrastructure. This is a real consideration that demands a solution as the percentage of renewable solar increases. I don’t deny the problem, but I disagree with their solution. The cost of maintaining the electrical grid infrastructure needs to be paid for.

The cost of a kW of electricity includes much more than just the cost of power, there are other costs such as the cost of transmission, distribution, cost of public purposes (free energy conservation classes for example), nuclear decommissioning, and others. In California it is illegal for utilities to markup the cost of power, the utilities purchase power on the wholesale market, selling it for the wholesale price plus the additional costs of transmission, distribution, maintenance and others (plus a profit on these additional items) in order to determine the retail value. I consider some of the extra costs to be highly questionable. One example of this is the bill to pay for the future decommissioning of defunct nuclear power plants. It seems to me those costs should have be included in the cost of power from them. Removing the cost of decommissioning those plants from the “cost” of operations biases the determination of whether or not nuclear power plants are economically viable. The cost for “power” is a small percentage of the overall cost of power to the customer.

So yes, there is an inequality embedded in their rate structure because net metering customers might not directly pay for the services that they enjoy. Perhaps the price differential between peak power rates and off-peak power rates isn’t sufficient to pay for all of the services. That would be an interesting thing to find out, but as far as I have been able to ascertain the CaPUC made no attempt to determine if there is an actual inequality or not because they didn’t investigate the impact of the differential between electricity’s value when produced at peak periods but used at off-peak periods.

It seems to me that a better solution than embedding the costs of delivery into the cost of a kW of power is to bill for the cost of the infrastructure separately from the cost of kW. For example, the infrastructure to support a 100 amp service costs x amount per month, while the infrastructure to support a 200 amp service costs 2x. The bill should reflect the actual cost of power plus the actual cost of providing the necessary infrastructure to deliver that power. However, determining how to partition the infrastructure costs isn’t obvious. Transmission, distribution and maintenance costs seem to be fairly fixed across the entire utility grid. Poles, wires and crews cost about the same regardless of how much an individual house uses. Maybe the solution would be a load based fee for everyone that hooks up. If a large industrial user requires special upgraded service, then they should pay for that as an “extra” cost. It seems fair for every customer pay a uniform basic “hook up fee” that covers the cost of the shared infrastructure. Costs for the power should be a separate fee on top of that.

The approach of changing from the infrastructure separate from the cost of power would result in everyone paying for the infrastructure. This approach is already used by many customers such as agriculture and many commercial users. For example, for agricultural users there is a monthly bill for hooking up to the service and a separate bill for the energy. The more capacity (kilowatts) they need the more the infrastructure costs to deliver that peak capacity – large users pay a higher amount to cover the\t additional infrastructure cost. Separating the cost of infrastructure from the cost of power is already being done in many power sectors, and it has been shown to work as a means of ensuring that users pay for their fair share of the cost of delivering power.

The fixed infrastructure costs (those not tied directly to the cost of power) are on the order of 50% of the total power bill. Perhaps everyone should pay that amount equally. For example, right now the average residential electric bill for PG&E in California is $276 per month. That means that the flat fee infrastructure cost should be about $138 per month. Perhaps all residential users should pay that flat fee plus the cost of the power that they use. I believe a “fair” system would change everyone for the infrastructure separate from the cost of power. Solar generated electricity should be evaluated as a “net metered” average so that the bill is for the amount of power that is needed beyond what the solar produces.

My suggestion of billing each customer for the cost of their share of the infrastructure raises the question of how to evaluate that share. I think a customer with a 100amp service should pay less than a customer with a 200 amp service. The larger the service the greater the cost of the physical part of the infrastructure (wires, support structures, switching stations, etc). An added bonus to charging for infrastructure based upon maximum load this is that it automatically creates a bonus for people to store their solar energy (perhaps in batteries), thereby reducing the size of the service they need (or their maximum load). It would also incentivize them to reduce their use through various modes of conservation. Limiting the size of the service to the maximum projected use would dramatically reduce the size requirements for infrastructure – putting us on the road to a renewable future. The current “fix” goes exactly in the opposite direction.

However, while this approach is “equitable” in terms of people actually paying for what they use, it shifts even more infrastructure cost from those with solar to those without because solar uses would need a much smaller service and therefore pay less for their fair share of the infrastructure costs. It would be “fairer” but would also increase the cost of electricity for those without solar. I suppose this problem of “unfair” costs will remain until such time that all residential users have solar. In cases where it is not possible to effectively install solar perhaps there is a means for local community sharing of solar arrays.

A similar problem is getting ready to bite us with road taxes being embedded into gasoline prices. The road tax is supposed to pay for the cost of the infrastructure (the roads). But those that don’t buy gasoline because they have electric cars don’t pay for the infrastructure (the roads) – a very bad situation. The cost of infrastructure needs to be put on the use of the infrastructure – miles driven (and weight), not gallons of gasoline used. The solution is to charge (tax) per mile driven (adjusted for vehicle weight). It would be a nuisance to have to report the mileage driven on tax forms, but it really would only have to be done once a year with taxes. Perhaps this could be done automatically with the new internet connected vehicles. Then everyone pays for what they get – roads.